Have you noticed that tasks and projects always take longer than you think they will? We have a tendency to underestimate how long something will take, even when we are aware of this tendency and try to compensate for it. This observation is known as the Hofstadter’s Law, which tie into the Planning Fallacy.

Hofstadter’s Law: It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.

Our difficulty with setting accurate estimates when planning illustrates one element of the optimism bias. In this article, we’ll cover what you need to know about the Planning Fallacy and how you can improve your accuracy in forecasting.

What is the Planning Fallacy?

The Planning Fallacy was first proposed in the report “Intuitive prediction: Biases and corrective procedures” by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1977. The Planning Fallacy is formally defined as “the tendency to hold a confident belief that one’s own project will proceed as planned, even while knowing that the vast majority of similar projects have run late” (Buehler, Griffin & Ross, 2004).

“The Planning Fallacy is that you make a plan, which is usually a best-case scenario. Then you assume that the outcome will follow your plan, even when you should know better.” – Daniel Kahneman

In other words, we tend to be overly optimistic when planning and not take into account knowledge about outcomes in similar cases. The results of these unrealistic project expectations are missed deadlines and blown budgets.

Real-world examples of the Planning Fallacy

A real-world example of the Planning Fallacy is the construction of Sydney Opera House, which was expected to be completed in 1963 with a cost of $ 7 million. The actual completion was not until 1973, and the cost ended up being $102 million (Sanna, Parks, Chang & Carter, 2005).

Another example is the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau bridge, which was set to open in 2016. Due to safety issues and construction delays it didn’t open until the end of 2018, with major cost overruns (Kuo, 2018).

You have probably experienced the Planning Fallacy in your everyday life as well:

- Planning to get in shape in an unrealistic amount of time

- Planning to get all cleaning done on Sunday evening – and failing

- Planning to do a lot of work during the weekend, but ending up not even looking at it

- Planning to spend a certain amount of money on vacation and ending up tripling it

- Estimating the cost of home renovations to be significantly lower than the actual cost

- And the list goes on and on and on..

So, why do we fall victim to the Planning fallacy?

Let’s dive into some of the proposed explanations behind the Planning Fallacy.

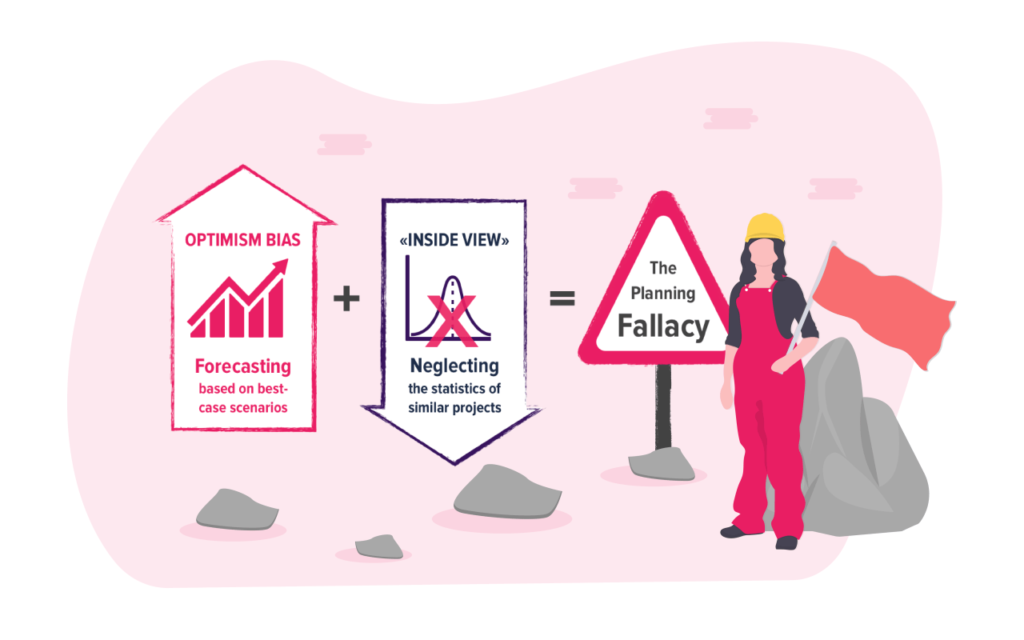

Optimism bias

Optimism bias is defined as “the tendency of individuals to expect better than average outcomes from their actions” (Reyck, Grushka-Cockayne, Fragkos, Harrison & Read, 2017). We overestimate the likelihood of positive outcomes and underestimate the likelihood of negative outcomes. A good example of this is entrepreneurs’ belief that their business will succeed, even though the statistics say otherwise. When it comes to planning, this bias often leads to overestimation of the benefits associated with a project and underestimation of the time/cost needed to complete it.

However, having an optimism bias isn’t all bad. According cognitive neuroscientist Tali Sharo, “people without an optimism bias tend, in most cases, to be slightly depressed at least, with severe depression being related to a pessimistic bias where people expect the future to be worse than it ends up being” (Dubney, 2018). Having an optimism bias can actually drive us and increase our willingness to explore new things. Would we ever try to go space if we weren’t overly optimistic that we would succeed?

Taking the “inside view”

According to Kahneman & Tversky (1977) one explanation of the Planning Fallacy is “the tendency to neglect distributional data, and to adopt what may be termed an ‘internal approach’ to prediction, where one focuses on the constituents of the specific problem rather than on the distribution of outcomes in similar cases”.

Taking the inside view when evaluating plans is likely to cause underestimation (Kahneman & Tversky, 1977). There is a high probability that something will go wrong in a project, even though the likelihood of each of the ways the project can fail is low. When focusing on everything that makes your project unique, instead of the similarities it has with previous projects, it’s difficult to foresee unanticipated events that can make the project drag on.

Strategic misrepresentation

Strategic misrepresentation, which is just a fancy term for lying, is another possible explanation to the Planning Fallacy. Strategic misrepresentation entails strategic and deliberate overestimation of benefits and underestimation of costs in order to increase the likelihood of getting approval or funding for a project (Flyvbjerg, 2008).

In contrast to the optimism bias, strategic misrepresentation is intentional. The results are however the same as with the optimism bias: inaccurate forecasting, inflated benefits and cost overruns. While deceiving people to achieve our goals is unethical, Daniel Kahneman made an interesting point in an interview on the Freakonomics podcast: “If you realistically present to people what can be achieved in solving a problem, they will find that completely uninteresting. You can’t get anywhere without some degree of over-promising.” (Dubney, 2018).

How to increase accuracy in forecasting

The causes of the Planning Fallacy gives us some natural implications on how to improve planning and project management. Let’s go through two methods you can use to increase accuracy when planning projects.

Take the outside view (Reference class forecasting)

One way to increase accuracy in planning, is by taking an external approach to forecasting. As mentioned above, this means basing your predictions on knowledge about outcomes in similar past projects (distributional information) instead of focusing on the unique features of your projects (singular information).

The technical name of taking the “outside view” is reference class forecasting. According to Kahneman (2011), this forecasting method requires the following three steps:

1. Identify an appropriate reference class

Find a class of past projects that are similar to yours. It must be narrow enough to be comparable with your project, but broad enough to statistically meaningful.

2. Obtain statistics for this reference class and use it to create a baseline prediction

What was the completion time vs estimated time for these projects?

By how much did the projects costs exceed the budgets?

Statistics on time and cost overruns in similar projects give you an indication on what to expect for your project.

3. Use specific information about your project to adjust the baseline prediction

In what ways are your projects different from the ones in the reference class? Do you have any reason to believe that your project will be more or less prone to the optimism bias than the projects in your reference class? Adjust your baseline prediction accordingly.

Perform a project pre-mortem (Prospective hindsight)

Another way to increase accuracy when planning projects, is to perform a project pre-mortem. This means imagining that an event already has occurred and work backwards to identify possible reasons for this outcome. Prospective hindsight can increase the ability to correctly identify reasons for future outcomes by 30 % (Mitchell, Russo & Pennington, 1989). By increasing awareness around the uncertainty of a future outcome, prospective hindsight can reduce the optimism bias and thus increase the accuracy of forecasting.

Here’s an example of how to perform a pre-mortem:

1. Imagine that your project has failed

Research suggests that people put more effort into looking back than looking forward.

2. Brainstorm all the possible reasons for why it failed

Some methods that can be used are SWOT analysis, PESTLE or risk analysis.

3. Address the threats and weaknesses you have identified

Discuss specific actions you can take to reduce threats and strengthen weaknesses.

4. Revise project plan accordingly

Use this information to improve the accuracy of existing project plan.

Key takeaways

1. The Planning Fallacy = Optimism bias + Inside view

The Planning Fallacy explains our tendency to plan based on a best-case scenario while neglecting information about similar projects, which results in unrealistic project expectations.

2. Most of us are subject to the optimism bias

Optimism bias is defined as “the tendency of individuals to expect better than average outcomes from their actions”. When it comes to planning, this bias often leads to overestimation of the benefits associated with a project and underestimation of the time/cost needed to complete it.

3. Taking an outside view to forecasting can reduce the optimism bias

Start basing your predictions on knowledge about outcomes in projects that are similar to yours. Statistics on time and cost overruns in similar projects give you an indication on what to expect for your project.

4. Prospective hindsight can increase the ability to correctly identify reasons for future outcomes by 30 %

Pretending that your project has failed and coming up with reasons why it would have failed can help you put away the best-case scenario and come up with more accurate estimates.

5. Simply being aware of the Planning Fallacy is not enough to stop us from falling victim to it

My estimate for finishing this article was actually last week – so I basically fell victim to the Planning Fallacy while writing about it. There you have it folks, the Planning Fallacy in action.

References

Buehler, R., Griffin, D. & Ross, M. (1994). Exploring the «Planning Fallacy»: Why People Underestimate Their Task Completion Times. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 366-81.

Dubney, S (Host). (2018, March 7) “Here’s Why All Your Projects Are Always Late — and What to Do About It (Ep. 323)”. In Freakonomics Radio.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2008). “Curbing Optimism Bias and Strategic Misrepresentation in Planning: Reference Class Forecasting in Practice”. European Planning Studies Vol. 16, No. 1, January 2008

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1977). “Intuitive prediction: Biases and corrective procedures”. Decision Research Technical Report PTR-1042-7746, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

Kahneman, D. (2011). “Thinking, fast and slow”. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kuo, L. (Oct 22, 2018). “World’s longest sea bridge to open, but only to drivers with a special permit”. The Guardian.

Mitchell, D.J., Russo, E.J., Pennington, N. (1989). “Back to the future: Temporal perspective in the explanation of events”. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 2(1), 25-38.

Reyck, B.D.,Grushka-Cockayne, Y., Fragkos, V.I., Harrison, J. & Read, D. (2017) “Optimism Bias Study: Recommended Adjustments to Optimism Bias Uplifts”. The UK Department for Transport.

Sanna, L. J., Parks, C. D., Chang, E.C. & Carter, S. E. (2005). “The Hourglass Is Half Full or Half Empty: Temporal Framing and the Group Planning Fallacy”. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 9 (3): 173–188.